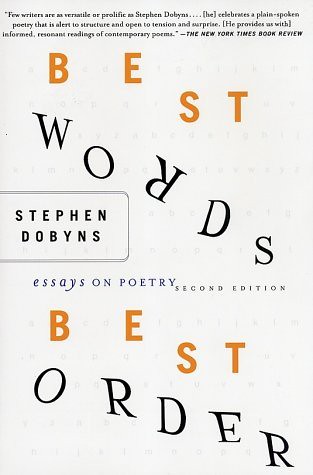

I am reading Stephen Dobyns' Best Words Best Orders: Essays on Poetry. I have long been looking for a book which would reflect on the process of writing poetry beyond the introductory stuff. It's not that they are bad, but personally, I don't have to work on pushing myself to sit down to write anymore. Neither does anyone else have to do the work of convincing me that in order to write, I need to read. Dobyns' book has been helpful so far. Although I have read only the first two chapters. One of the things he does in this chapter is to see the work of the poet through the figure of the court jester. Dobyns writes:

The jester laughs at the king, yet the jester himself has nothing. The dwarf reminds me of that mixture of gall and humility that one must have in order to write.

I agree whole-heartedly with the “gall and humility” part. For me, it translates to this strange combination of rejection, intellectual arrogance, hard work and plain old humility. I know I cannot really create what I want to create without rejecting a lot of stuff in this life-- social ideological and aesthetic. In fact, the way I think about it, the three are intertwined. I need to have the arrogance in me to stay true to my decisions, to explain them to people without flinching. But rejection alone, or negation alone has never done it for anyone. It won't do for me either. So, there is this immense need to come back to the work-table every day, make myself a cup of tea or coffee, munch on a banana, and just write. Sometimes read. Take notes. Look up from what I am doing to think, to process, to figure out more. Needless to say, I cannot really stick to this schedule of hard-work until and unless I also have an open mind to critiques and criticisms. The essential knowledge that whatever I am doing is nothing compared to what can be done. I am not writing about accepting all criticisms blindly, but there is a need to take all criticisms seriously, to think through them, and then reject it with a certain kind of intellectual modesty. As I am learning, criticisms/critiques are also ideological, historical and cultural in their very basic nature. So, I cannot really take them at their face-value. But at the same time, they deserve time and thought, a seriousness of consideration.

Anyways, what is disturbing me a little bit is Dobyns' attempt to see the court jester as having nothing. Of course, the jester has something very important-- the access to the royal court. His work, as I see it, is more of subverting the norms of the monarchy while staying within it, while continuing to enjoy its privileges. And there is a certain kind of utility to it. But what about the artists who prefer to stay away from the court altogether? Who sings and tells stories to people who will never get to see the court? I am not saying, that the two spheres are two air-tight containers, for, it's often that one makes way for oneself inside the court through singing to people. In the same way, there might be poets and story-tellers who make the conscious choice to be one or the other. So, to put it in a more rounded kind of a way, what relationship a poet or artist or story-teller chooses to have with the court, it all boils down to the specific context. But what I am trying to say that, it is symptomatic that Dobyns begins his book with this particular figure. I think, it reveals a lot about the politics of much of mainstream white, male (and sometimes women) American poets to the culture industry. It's all about trying to find one's space to laugh while staying within its logic. It's rarely about changing or moving beyond the rationality of a capital-centric culture-industry altogether.

No comments:

Post a Comment