Thursday, November 25, 2010

Longer Poems, Readers'/Editors' Expectations

About the workshopping part, I am less sure. Is it appropriate to impose on my readers too long a work? Besides, most of the beginning and intermediate writers who come to the workshops, are also learning to be readers. And here, I do have a distinct advantage over most of them, being a Phd candidate in Literature and what not. My graduate school years have succeeded to give me a kind of experience in critical reading of literature which I can't expect most people to have. But then, the question is, what to do? How to workshop my longer poems? If those are the only ones that I am writing?

Sunday, November 21, 2010

Duck Recipe

The duck sat on my freezer for too many days. Meanwhile, I kept looking for recipes in the web. Most of them seemed too complicated for my grad-student kitchen. And then, I just decided to give it a try. I mean, you can't really go too wrong with the South Asian spices. Slow-cooking makes everything delicious, and somehow I happen to know duck wings should be cooked longer than chicken wings. So, here is my duck recipe. I still need to find a snazzy name for it. But for now, I will stick to the ubiquitous curry.

Friday, November 19, 2010

Revelation Friday

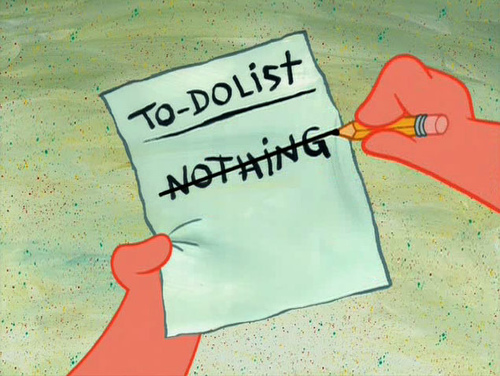

I have been busy writing grants and fellowship applications for a while now. I don't do a very good job of advertising my project or myself. So this is stressful. Also, I have lots of other bureaucratic things to take care of. I am not good in dealing with these either. Besides, there is also the anxiety. What if...what if nothing comes my way next year...how will I survive...how will I finish my dissertation...all in all these are not the happiest times for me. But I am trying to focus and take one thing at a time. It does feel good to be able to take care of my things from the to-do list. And I have been. But what is missing is that nice feeling of getting done.It's not that I am slacking off. It's just that I have a horribly LONG to-do list to take care of.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Why Myths? Why Fairy Tales?

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Putting Virginia Woolf in the Mix

I have been hesitant about putting the Virginia Woolf-A Room of One's Own poems in my collection. The collection, after all, is an attempt to re-write myths, folklores and fairytales. So wouldn't it be weird to put my series on A Room of One's Own in there? But then, I did. Because, while working on this collection, I have often felt the need to expand the meanings of the word myth. If colonialism hasn't been a myth, then what has been? If elite white feminism isn't a myth, then what is? As I worked through the poems, I kept wondering, myths are myths, after all, no? A myth is a representation, that is. A way to inscribe a mythmaker/writer's desires, dreams, frustrations and aspirations within the body of a story. One can say, it's not the real thing in that sense. Just a story. Something imagined. Constructed. Then isn't it going to incongruous to mix historical figures like Virginia Woolf with mythical figures like Cinderella and Briseis?

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Review:The Heart's Traffic by Ching-In Chen

Ching-In Chen’s debut The Heart’s Traffic: a novel in poems defies all attempts of strict categorization. As a “novel in verse”, Chen’s collection is neither an attempt to explore through poetic forms the fragmented nature of human lives and existence through abstraction in a language that is beyond the boundaries of our everyday, nor is it an attempt to write in seamless narrative a well-defined story with neatly identifiable beginning, middle and an end. Instead, Chen, who describes herself as a “multi-genre, border-crossing writer” and a community organizer, offers us a bildungsroman told in poems which themselves refuse to stick to any linear understanding of chronology.

Divided into four sub-sections, on the outset, Chen tells us a familiar story – the coming-of-age of an immigrant Chinese girl. Xiomei, who is haunted by the death of her best friend, Sparrow. It is in her attempt to explore the psychic landscape of Xiomei’s mind that Chen also ends up exploring other issues such as the history of indenture, the intertwined nature of family history and immigration history, race, sexuality, gender. In fact, in Chen’s poems, all these seemingly disparate strands brush against each other to form a complicated quilt where the “personal”, the “aesthetic” and the “political” do not remain confined within strict compartments. Needless to say, Chen does not flinch from writing about “big issues.”

Think of the opening poem “Cooled Ghee: a riddle.” Written in the form of a prose-poem, the poem invokes the history of the Chinese coolies in the Americas:

Long ago, two temporary fathers lived in an unmentionable land far from home. Under the tear-dry sun, the thin father from the North sang the songs passed down from his youth in his clear voice. The tall father from the South collected the elements of water, sand, dirt, and green for his stories with no end, no matter how wide the field grew in the night while they mumbled to their lost families. When the almond-colored father bent his waist to the rhythm in the field, his legs grew into tree trunks (17).

The use of the form of a prose-poem allows Chen to tell a story without losing its serrated edges – in metaphors, allegories and symbols. Thus, without being too obvious or didactic, the collection establishes one of the primary themes that will be repeated throughout the book—racialized labor and the role it plays in the cultural construction of the Americas in general, and more specifically, United States of America.

Later, in the book, Chen continues with the theme in her poems “Ku Li”, “Coolie: A History Report” “Coolly: a riddle.” The first one, a riff on the word “Coolie”, and the second, an invocation of a middle-school or high-school student’s social science project work together to impress upon the readers the fact that the history of Asian indenture in the Americas, and more specifically in USA, has been erased from the official history.

They

built the

railroad, but

couldn’t

go

to

the party.

They

were

sad

and

mad.

[43]

Obviously, Chen, here is exploring something as big as economic exploitation. But what is significant is that, she does it without falling back upon sentimental social realism. In fact, it is the very imagery of the coolies not invited to the party that prevents Chen from falling into the usual trap of sentimental protest poetry, while retaining the essential framework of social justice and anti-exploitation poetry.

Juxtaposed with the trauma of indenture of her ancestor, is Xiaomei’s own trauma of immigration to San Francisco. Here too, Chen explores all the usual issues of a post-colonial/ethnic poetics – colonial language, exoticization of Asian female bodies, loss of love and most importantly, what it means to be a queer woman of color. For example, in the poem entitled “Names”, Chen writes about the trauma of trying to learn a new language:

First to let go

of the murderous tongue,

end of the intimate and divine source

of the esophagus,

trained in the schoolbacked

wooden chair of youth,

ruler whack of pronunciation.

[38]

It is also not hard to see how, for Chen, writing about the trauma of language-acquisition is also a way to write about the traumatic nature of the very classroom itself. Or, educational institutions in general. A few poems later, in “A True Tale of Xiaomei”, she writes, “At school the next day, the girls would gather ‘round and I would unfold/The Great Outlandish True Tale of my pathetic mother,/ married off at age three,/ to an evil rich man as second wife/concubine./ How she squeezed sorrow out of her pounding chest./ How he beat her for that first daughter (me!)” Obviously, one can locate in here the usual re-cycled tales of an Asian/Chinese woman’s victimization repeated in here, but what is especially significant, is that it’s Xiaomei who participates in that myth-making. Thus, the cultural agency is shifted on to the Asian woman-writer herself, who participates in a form of self-Orientalization, only to debunk that very impulse later on in the same poem:

Never having a lover with my own family face,

I headed home to empty bed.

I cried for all the erasures within myself,

for the sand I had thrown on my mother’s memory,

for my hard back.

[52]

Thus, the tale that Xiaomei had churned out for her classmates about her mother, was, in reality, a form of erasure within herself. An erasure that is replicated in her inability to find a woman-of-color/ Asian woman to love. “Never having a lover with my own family face”, thus, becomes a somewhat indirect way to write about the essential whiteness and embedded racism of many of the queer communities. Xiaomei, thus, tries to make sense of her life within multiple forms of loss and amnesias.

Chen does not believe in making it easy for her readers. Thus, she does not explain herself, nor the cultural contexts she writes from. Yet, the poems of the novel write themselves in multiple forms—haiku, haiboun, ghazal, villanelle, sestina. The range is impressive, and reminiscent of the multiple cultural/historical/ideological communities/voices Chen is writing about. It is, as if, Chen is committed towards exploring the essential hybridity of poetic forms, in the same way she is committed towards exploring the complexity o the material she is dealing with.

And despite the complexities, Chen rounds off her verse-novel with a kind of hope : “Xiaomei dreams herself a clearing of green,/ a gathering of cool stone,/ a locking gate.” As she goes on to list the things Xiaomei dreams about, as readers, the readers ease themselves into a nicely-closed arc which, while preventing itself from providing a traditional novelistic climax, does offer some place from where “bruise-haired” women can begin to hope to be raised to “sea of sky.”

What Happened During the Hiatus

1. The first draft of the chapter 2 of the dissertation was completed, feedback received from the writing group. Now I need to go back to it and do the revisions before I turn it in to my co-directors again.